Native grains bring future potential

Indigenous Australians have been eating native grains, plants and animals for an estimated 60,000-plus years. Thousands of bush tucker sources provided them with an abundance of meats, fruits, vegetables, nuts, roots, seeds and insects. But the use and availability of native Australian foods was drastically reduced by white colonisation. This introduced European farming systems and foods, restricted Indigenous Australians’ access to traditional lands and destroyed large amounts of native habitat. Incredibly, until the 1990s, the only native Australian food being cultivated commercially was the macadamia nut.

But with climate change and an exploding population creating a need for more sustainable food systems, experts are now looking to traditional Indigenous agricultural practices as a potential solution. Farming native foods would not only provide Australia with a more environmentally friendly way to produce nutritious food; it’s also a chance to celebrate a long-overlooked and misunderstood food culture. Further, it could provide more Indigenous Australians with culturally sustainable economic opportunities.

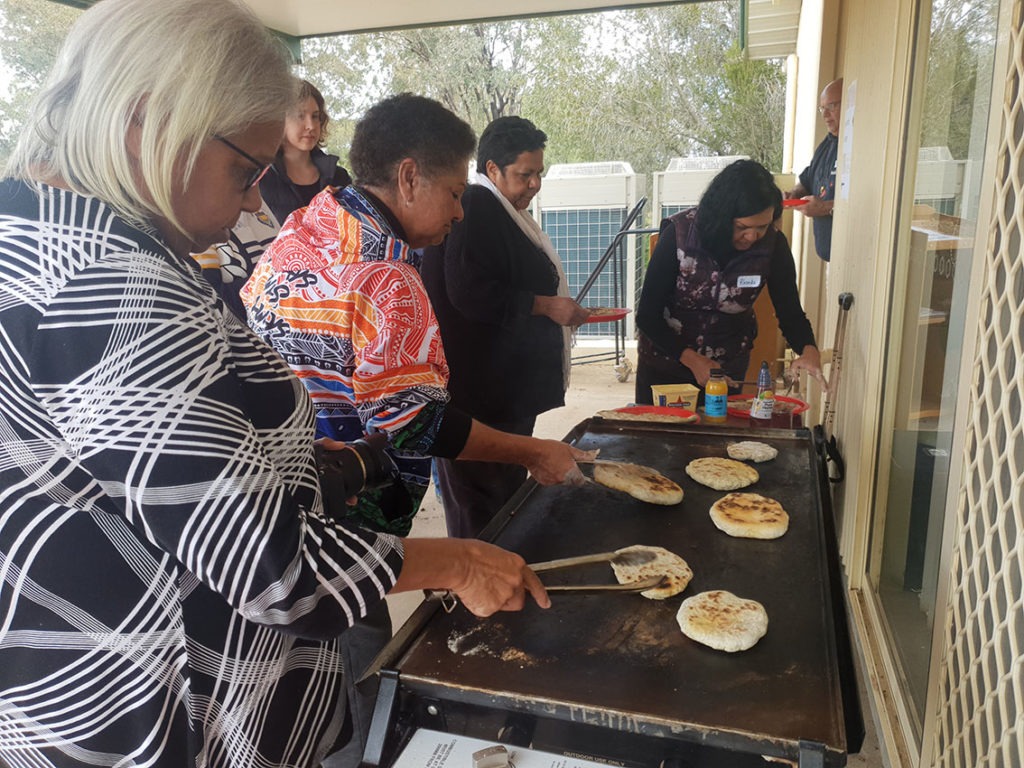

Making bread with dancing grass

Black Duck Foods is an Indigenous social enterprise founded by Indigenous author and native food expert Bruce Pascoe. It’s working to reengage people with traditional agricultural practices and create native Australian food systems. The goal is to use the business as a pathway for promoting economic development for Indigenous Australians.

“Black Duck Foods was created in response to a number of different factors,” says Black Duck Foods General Manager Chris Andrew. “One most glaring one is the fact that Indigenous Australians only see about one percent of the bush tucker revenue generated each year. We’re keen to try and create systems where that value is better placed. More equitably placed – back with First Nations people.”

Black Duck Foods predominantly farms native grasses such as mandadyan nalluk (dancing grass). It also grows native tubers such as the yam daisy or murnong. These are foods that come from Yuin country on NSW’s south coast. The business is working to find the most culturally, environmentally and economically viable ways to farm these foods. That way, others who come after them won’t have to start from scratch.

“We’ve gone through food safety regulations; we’ve looked at harvesting, threshing, processing and milling techniques,” Andrew says. “We’re looking at the full farm-to-plate story, so we get a better handle on the industry. Also so we can ensure that at each point, there’s an opportunity for employment and enterprise for Indigenous Australians.”

Sharing the knowledge

Black Duck Foods has recently been working with the University of Sydney Institute of Agriculture, consulting on a study that investigated the environmental, economic and cultural viability of farming native millet on Gamilaraay country in western NSW.

“Gamilaraay and Yuwaalaraay country in north-west NSW is one of the largest Aboriginal language groups in Australia,” says Dr Angela Pattison, study leader from the Institute of Agriculture Plant Breeding Institute at Narrabri. “They are proudly known as grass people.

“This region is now home to some of Australia’s best-quality agricultural land. Farmers here are major exporters of crops such as cotton, wheat and pulses. However, the region historically produced native grains such as Mitchell grass and native millet. These were ground up and made into fire-roasted bread by traditional owners for thousands of years.”

A matter of trust

During the study, Dr Pattison consulted with the local Indigenous community to see how they felt about commercialising their native grains, known as dhunbarr in Gamilaraay.

“The feedback we got was overwhelmingly, ‘Yes, please, we need to bring these foods back’,” she says. “They were very keen. But there were a lot of questions about how they would bring them back. How would they benefit from bringing them back? There was a general feeling that commercial viability sometimes passes them by.

“There were also some cultural questions. If they share knowledge on which grains are edible, or how to cook them, what’s going to happen to that knowledge that they’ve developed over thousands of years? If somebody else then benefits from that knowledge, how does that work for them?”

Andrew explains that capturing the potential of native foods is often done at the cost of the people who hold the knowledge of that food story.

“One of the perennial issues is that we get a lot of interest from industry,” he says. “But there’s no reciprocity. They’ll come, and it’s like, ‘How do we steal more knowledge?’

“It’s a testament to Australia, and our humanity, whether we continue to condone the theft of knowledge; to allow it to grow. Or do we stop and figure out how to equitably share this knowledge back with First Nations people?”

Saving the present with the past

Reintroducing native grasses could also lead to huge benefits for the land. It provides food for native animals, birds and insects, as well as the microbes and worms that live in our soil.

“The main environmental benefit of bringing back native grains would be the biodiversity,” Dr Pattinson says. “But there are also climate change benefits such as soil carbon sequestration. Also, the benefits of growing perennials, rather than annuals, for cropping. The environmental benefits of having a plant living all year round are significant. For biodiversity, for water infiltration into the soil and keeping the soil temperature down, because you’ve got plants covering it all the time.”

Re-establishing our landscapes and reintroducing more native ingredients into Australian food systems certainly has enormous potential. However, it’s not an overnight proposition. Logistics aside, much work needs to be done with Indigenous communities to ensure they benefit from the use of their foods as well as their knowledge.

“But it’s not exclusive,” Andrews says. “It’s not just for them. The benefits are widespread to all of Australia. It’s not a First Nations-only story, it’s a First Nations story. A 60,000-plus-year-old culture that we can all learn from and all benefit from. It’s gold.”