Does the Health Star Rating work?

It certainly has its detractors. But new evidence has emerged that food labelling using the Health Star Rating system can encourage food manufacturers to improve their product nutrition. However, University of Melbourne experts say the star labelling system must be compulsory if it’s to make a real difference to public health outcomes.

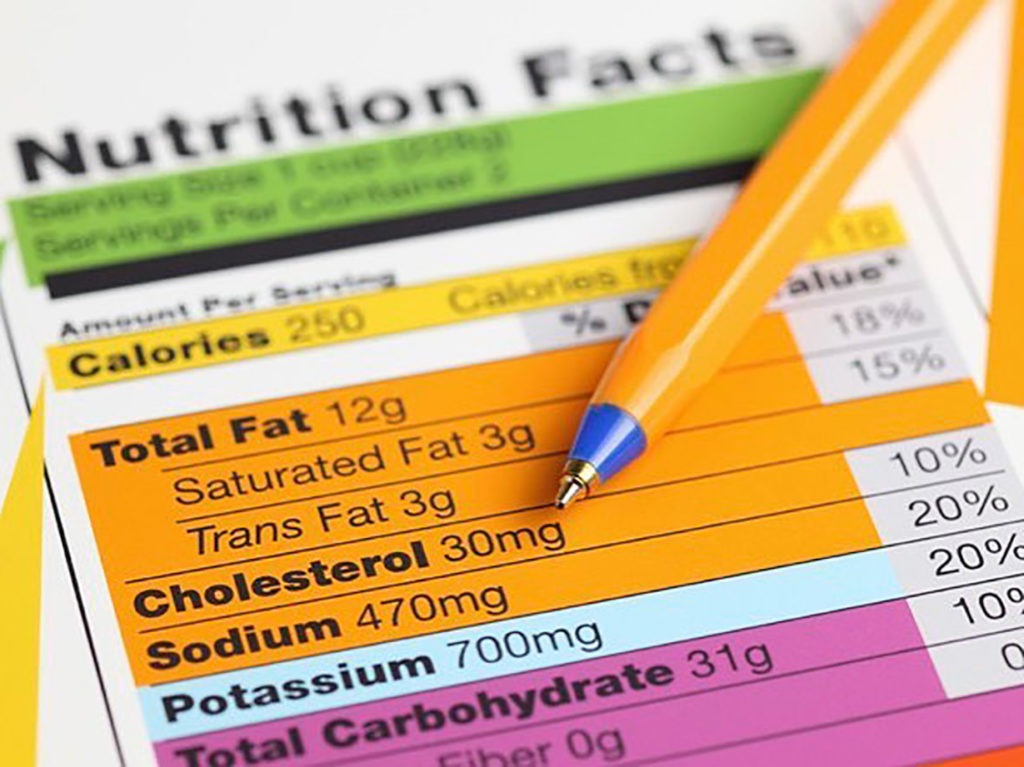

Nutritional information is mandatory on the back of packaged Australian and New Zealand foods. However, Health Star Rating labels – which rate a food from 0.5 (least healthy) to five (most healthy) stars – are voluntary.

Crunching the numbers

A team from the University of Melbourne, the University of Auckland and The George Institute for Global Health analysed the nutrition information of 58,905 packaged foods in Sydney and Auckland supermarkets each year from 2013/2014 to see if the Health Star Rating made a difference to how the food industry formulates food. Using the Health Star Rating calculator, they also scored unlabelled products to allow control comparisons.

Products that elected to display the rating on their product packages were 6.5 and 10.7 percent more likely to increase their score by 0.5 stars than those that didn’t display the stars in Australia and New Zealand respectively.

Small change, big impact

Australian products with a Health Star Rating showed a 1.4 percent decline in salt content, and a 1.1 percent decline in sugar content. Meanwhile, an average product with a Health Star Rating that scored 0.5 to 1.5 stars dropped its overall energy value by 1.3 percent.

Lead study author, University of Melbourne Research Fellow Dr Laxman Bablani, says while these improvements might sound very small, even modest changes could potentially lead to big health impacts at a population level.

“If the labels were compulsory, the impact could be much greater,” he says. “Health Star Rating adoption by unhealthiest products was less than half that of healthiest products.”

Some examples of positive reformulation include:

1. A popular flavoured cracker now has six% less fat and roughly 10% less sodium per 100g than before it adopted HSR labels in 2016. This took it from 1.5 to two stars.

2. Several instant soup varieties cut sodium and energy to increase their rating from three to 3.5 stars in the year they were labelled.

3. A major supermarket branded barbecue sauce cut sugar by 9.6% in 2017 when it adopted HSR labels.

Senior study author and University of Melbourne Professor Tony Blakely says compulsory Health Star Rating labels could improve unhealthy foods.

“There is little incentive for manufacturers to label unhealthy foods voluntarily,” he says. “If it was compulsory, the quality of packaged food would improve. Consumers may also possibly make better choices about healthy and unhealthy foods.”